Walis Johnson

Artist, Brooklyn, New York, United States of America

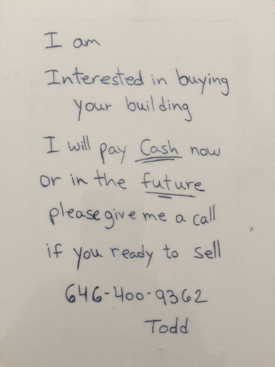

On October 24, 2013 my mother passed away. The next day I found a handwritten note folded into the gate of her brownstone—the home where I grew up and now live. The note said:

Figure 1: Letter. Photo credit: Author.

Still raw from my loss, I angrily threw it in the trash. That year, I received dozens of similar notes and phone calls from realtors hungry for a potential sale. Soon my anger turned to curiosity: Why had real estate speculation become so aggressive? What did this have to do with neighborhood gentrification, housing policy and the long history of racial housing segregation in America? These questions were the catalyst for a series of artistic walks and participatory art works called The Red Line Archive Project (2016-ongoing). The Red Line Archive Project engages Brooklyn residents in a conversation about race and the role of the 1938 Federal Home Owners Loan Corporation’s Red Line Maps, which helped to create the segregated urban landscapes of New York and 238 other cities across America.

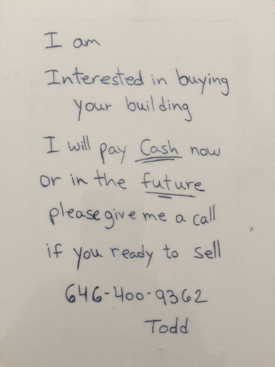

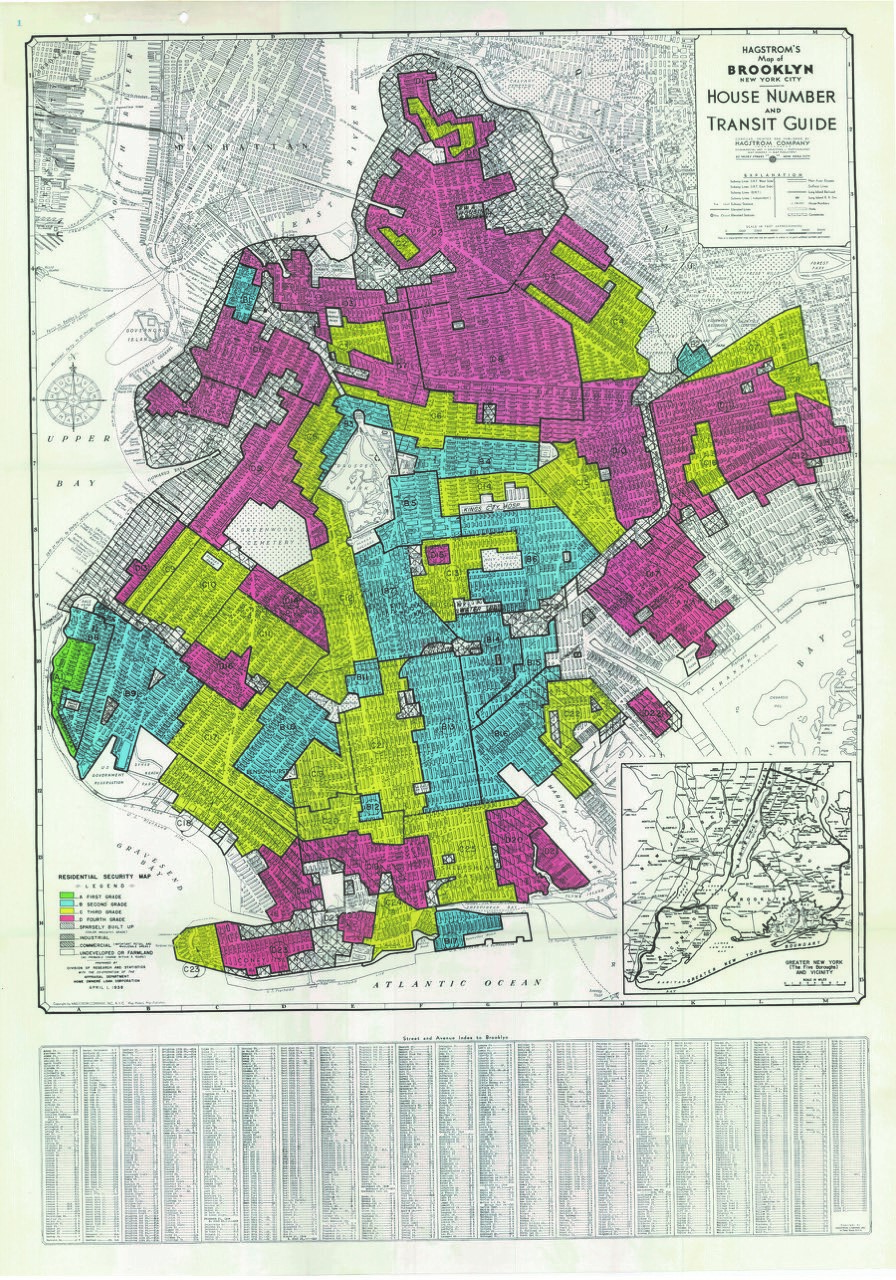

To redline a neighborhood is to starve an area of economic investment, home mortgages and public services based on the race or ethnicity of people who live there (Woodsworth, 2016). Created in 1938 by the Federal Home Owners Loan Corporation, Red Line Maps were used to exclude people of color, usually black people, from the greatest source of wealth creation in America – home ownership. The maps were color-coded: green, blue, yellow and red. Green indicated the best areas for investment which were white areas with the most restrictive racial covenants written into deeds; blue areas were still attractive for investment; yellow, declining; and, red stood for so called hazardous areas inhabited by European ethnics prior to WWII and after the war, by black citizens and other people of color. This insidious policy played out over time, impeding black home ownership, wealth accumulation and full participation in the US economy and political system. Yet, traces of redlining are evident today in myriad forms of economic and housing discrimination, inequitable education, policing, and poverty. Vast political, cultural and social divisions in the US can, in part, be traced to the segregated geography the policy promoted (Coates, 2014).

The Red Line Archive includes visual, material and ephemeral artifacts collected during four walks along the perimeter of formerly redlined neighborhoods in north and central Brooklyn. These areas once provided affordable homes to working class ethnics, black people and immigrants of color; now, ironically, they are the epicenter of some of the most expensive and aggressively gentrified real estate in the city. Historian Jelani Cobb once wrote in the New Yorker, “The past haunts along the periphery” (Cobb, 2015). If this is true what evidence of past redlining are still visible today? What emotions, insights and visual metaphors might arise as I walked along the periphery of the original 1938 Red Line Map of Brooklyn? Equipped with camera and journal, I walked around the perimeter of former redlined neighborhoods in search of clues.

Figure 2 and 3: Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) Brooklyn Red Line Map and Legend, 1938 (as cited in Nelson et al., 2019). In the public domain.

I identified what I thought were hidden traces of redlining in the landscape. As areas changed from red, to yellow, to blue on the map, I noted changes in soundscape, architecture and physical condition of neighborhoods. Industrial sounds of rapidly gentrifying Williamsburg and Bushwick gave way to the quiet serenity of what was once the white middle- and upper-class enclave of Highland Park, which borders Queens. From there I plunged into East New York, walking underneath the relentless rumbling and clanking of its elevated trains that echoed through garbage strewn empty lots and past community gardens that lay below. The gardens sprang up in the 1970’s as a sign of resistance (and resilience) to years of deliberate government neglect (Thabit, 2003, p. 2).

Today, East New York has been newly rezoned, paving the way for greater gentrification, infrastructure and public services to flow. Yet, as I walked, the landscape revealed signs of ambivalence and optimism about its future: one philosophical graffiti artist tagged a wall with a yin-yang symbol; a nearby homeowner had placed a sign stating ‘love is all you need’ on the front window, offering an enduring vision of hope and love to local residents who lived through very tough times.

Walking through Crown Heights I saw churches that were once Jewish synagogues. These institutions became church homes for African Americans and others who migrated to the area after previous groups of white ethnics dispersed to racially segregated suburbs.

Figure 4 and 5: Greater Bibleway Temple edifice and cornice with the Star of David. Photo credit: Author.

A core feature of the policy was dis-investment and abandonment of minority neighborhoods by banking and insurance industries. Why locate banks where no loans were made? While walking, I noticed that banks were still quite rare: as I travelled through Bushwick there was only one Capital One bank along a commercial stretch of Wycoff Street, the major commercial street in the area. Later, using an informal count via the Internet, I learned there are 11 banks in the entire Bushwick area compared to 20 along one commercial street in toney Brooklyn Heights, which was shaded green on the Map. Visual metaphors leapt out at me as I traversed west on Eastern Parkway. Adjoined homes, one dark, one light, reminded me of racial divisions artificially engineered by redlining (see Figure 6), where neighborhoods sometimes turned from majority white to majority black in a matter of months (Thabit, 2003, pp. 29-48).

Figure 6: Eastern Parkway. Photo credit: Author.

You’ve got to walk / that lonesome valley / Walk it yourself / You’ve gotta go / By yourself / Ain’t nobody else / gonna go there for you / Yea, you’ve gotta go there by yourself.

-Traditional Gospel Song

To walk the 1938 red line map is to perform and embody a way of knowing, on a profound emotional and sensory level, the experience of racism and historical loss that lives on in the urban landscape. In this sense, my walks proved painful, enlightening and life altering. It’s an experience I feel compelled to share with others who don’t know about the trauma of this history.

Figure 7: The Red Line Mobile Archive, 2016. Photo credit: Author.

Figure 8. Archive Detail, 2016. Photo credit: Author.

As an artist, I continue to conceive new ways to engage others in understanding their political, historical and material relationship to redlining. The project continues with Red Line Mobile Archive (see figures 7 and 8) and Red Line Labyrinth (see figures 9 and 10). These latest iterations of the project are another creative attempt to, in a sense, ‘re-map’ the practice of redlining through walking. The Red Line Labyrinth is a contemplative public walk performed in neighborhoods at the forefront of gentrification. As participants walk the labyrinth and share their reflections, they enact a deep community conversation about historical memory and their experience of redlining today. Through all of these different elements, The Red Line Archive Project is creating a new collective narrative of the politics and poetics of place and home, of property and citizenship. It is an attempt to reclaim our right to the city, which the racist legacy of Red Line Maps so brutally denied.

Figure 9: Red Line Labyrinth at Weeksville Heritage Center, 2017. Photo credit: Murray Cox.

Figure 10: Red Line Labyrinth at Weeksville Heritage Center, 2017. Photo credit: Murray Cox.

Coates, T. (2014, October 17). The racist housing policies that built Ferguson. The Atlantic. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/

Cobb, J. (2015, August 15). Race and the storm. The New Yorker. Retrieved from www.newyorker.com/

Nelson, R. K., Madron, J., Ayers, N., Hayes, K., McKinney, C., Reistle, L., Connolly, N. D. B. (2019). Mapping inequality: Redlining in new deal America. American Panoroma. Retrieved from https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=1/35/-266&text=bibliograph

Thabit, W. (2003). How East New York became a ghetto. New York City, NY: New York University Press.

Woodsworth, M. (2016). Battle for Bed-Stuy: The long war on poverty in New York City. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Walis Johnson is a filmmaker, educator, walker/researcher interested in the intersection of documentary film and performance whose work documents the urban landscape through ethnographic film, oral history, and artist walking practice. She holds a BA in History from Williams College and an MFA from Hunter College, in Interactive Media and Advanced Documentary film.